Initial Impressions and Review of Hugh Houghton's new Textual Commentary

This will become one of two new standard reference works and a great starting place for textual research

I’ve had a chance to dip into Hugh Houghton’s new Textual Commentary a bit and sample some significant variants.

Initial thoughts/observations:

Physically — it comes in at 590 pages + 36 pages of introduction, although it is the same small size as Metzger’s Textual Commentary and uses the same very thin “Bible-like” paper, so text from the other side “bleeds” through. Metzger’s edition had a leather cover, but this has a normal hardcover, so it feels less premium.

Houghton’s Textual Commentary is not a reporting of the UBS6 committee’s decisions, but it’s his own work. The UBS6 adopts all ECM textual changes in Mark, Acts, and Revelation. But elsewhere, the text remains the same as UBS5/NA28. So the UBS6 committee didn’t make any textual decisions — they simply adopted the ECM’s changes to NA28. Houghton does try and defend the UBS6 text while “indicating which of the alternative readings are worthy of serious consideration” (p. 35*).

The UBS6 editorial committee did, however, re-evaluate the letter ratings, so often levels of certainty will change between UBS5 and UBS6. And some readings with brackets in UBS5 were changed to having no brackets in UBS6. And there are still some diamond readings where the UBS6 committee did not reach a decision, but this is far lower than the number of split readings in the ECM volumes. There are only 47 diamond readings in UBS6. Compare with ECM Mark (126 split lines), ECM Acts (155 split lines), ECM Catholic Epistles (43 split lines), and ECM Revelation (106 split lines). Thus, whereas the ECM volumes present a far more uncertain text than UBS4/NA27, the UBS6 moves back towards a more confident text overall.

It’s very helpful that Houghton is aware of so much of the secondary literature, so he cites many places where you can go to find further discussion. And it’s not just pointing to ECM Textual Commentary, but to journal articles, book chapters, discussions within books on other topics, etc. Metzger didn’t do this. Houghton’s commentary becomes a very good first stop on the way to more textual research.

Houghton doesn’t attempt to list many witnesses, but consistently refers the reader to the Text und Textwert data. This is probably the right move since abbreviating the data can distort the external evidence. But not many people have access to all the Text und Textwert volumes. The UBS6 has its own apparatus, of course, but Houghton does discuss 224 passages not covered in the UBS6 apparatus.

Like many British commentators, Houghton’s style is to lay out all the options as fairly as possible — but often leaves you in suspense. You read through an entry, get a good sense of the different options, but you have no idea which option Houghton prefers. The letter ratings do help a bit (e.g. {D} rating means Houghton doesn’t prefer the main text reading like at Rom 5:1 and 2 Pet 3:10). But there are only 18 {D} ratings total in UBS6.

Houghton consistently interacts with the SBLGNT and THGNT and highlights when they differ from the UBS6 text. This gives the correct impression that there are viable alternative options. It de-monopolizes the UBS text and encourages readers to consult multiple editions. And it’s an act of “scholarly humility” in highlighting the work of other textual scholars.

Random Sampling of Textual Commentary

Matt 5:22 omit εἰκῆ {B} rating (UBS5 also had {B} rating). Houghton cites three studies arguing to include εἰκῆ. But εἰκῆ is missing from witnesses “which are early and weighty” (p. 8). Notice him using the term “weighty” witnesses rather than “Alexandrian.”

Mark 1:1 include υἱοῦ τοῦ θεοῦ {C} rating; UBS4/5 read υἱοῦ θεοῦ with {C} rating. Houghton gives arguments from the CBGM and cites several studies. There is a discrepancy here between the ECM and UBS6 editors: ECM had no uncertainty (i.e. no split line reading) in printing υἱοῦ τοῦ θεοῦ, but UBS6 editors have a {C} rating.

Mark 1:41 σπλαγχνισθεὶς {B} rating. Since ὀργισθείς is only found in the Greek-Latin manuscript Codex Bezae and a few other Latin witnesses, Houghton has a helpful observation: “the similarity between the two words in Latin (miseratus ‘moved with pity,’ iratus ‘moved with anger’) provides a means by which the word ‘anger’ may have been introduced into the Greek side of a bilingual manuscript” (p. 76). Houghton cites many studies here.

Luke 22:43-44 (Jesus sweating blood) {B} rating. Sounds like these verses will be removed from the text whereas NA28 had double brackets around the verses. UBS4 had {A} rating for omission, but UBS5/6 have {B} rating for omission, so Houghton is a bit less certain about omission.

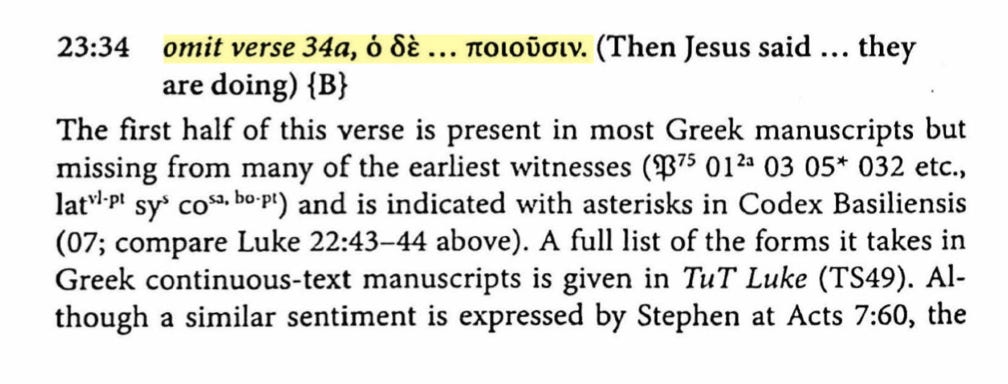

Luke 23:34a (“Father forgive them…”) {B} rating. Sounds like this will be removed from the text whereas NA28 had double brackets around it. UBS4/5 had {A} rating for omission, but UBS6 downgrades to a {B} rating and cites literature arguing for its originality.

John 1:18 μονογενὴς θεός {B} rating (same rating as UBS4/5). Houghton explains his doubt: “given that both [θεός and ὑιός] were customarily abbreviated as nomina sacra, there remains a slight possibility that, at an early point, ΥC (with an overline) might have been misread as ΘC.” (p. 198)

Romans 5:1 ἔχομεν {D} rating (UBS4/5 had {A} rating). Houghton’s {D} rating is quite significant since UBS4/5 both had an {A} rating for ἔχομεν; high confidence has shifted to high uncertainty. Houghton gives arguments for both the indicative ἔχομεν and the subjunctive ἔχωμεν and doesn’t come across as favoring one over the other. Houghton is the editor for the ECM of Romans, so I suspect he will print a split line reading here. On ἔχωμεν, he says: “it may be noted that this verb is co-ordinated with the subjunctive καυχώμεθα (‘let us boast’) in the following verse, and there is a further subjunctive at the beginning of the next sentence” (p. 388).

2 Peter 3:10 οὐχ εὑρεθήσεται {D} rating. Houghton focuses on the NA28/ECM/UBS6 conjecture (οὐχ εὑρεθήσεται) and the text adopted in THGNT (εὑρεθήσεται); he doesn’t really side with either, hence the {D} rating. However, the changes in uncertainty are interesting: UBS4 had {D} rating, UBS5 had {C} rating, and UBS6 goes back to the {D} rating of UBS4. This uncertainty contrasts with the ECM editors, who confidently adopted οὐχ εὑρεθήσεται (i.e., no split line).

Overall? Comparison to Tyndale House Textual Commentary?

Houghton has produced a great replacement for Metzger (but Metzger will still be useful, for example on subscriptions!) Houghton’s work will become a standard reference work and a good starting place for textual research since he points to so many additional studies.

Now we await Dirk Jongkind’s Textual Commentary on the Tyndale House Greek New Testament. I’ve read through large parts of the draft and I can say that Jongkind and Houghton will complement one another well with different approaches within reasoned eclecticism (e.g., no CBGM in Jongkind, more weight on early evidence and scribal habits in Jongkind, the reader almost always knows which variant Jongkind prefers). And Jongkind will provide many appendices with grammatical/syntactical studies — such as the addition/omission of Amen at the end of books (this one is my favorite), the use/non-use of the article with proper names in John’s Gospel, and discussions of spelling issues.

CLARIFICATION: Peter Gurry noted how UBS6 will not omit any verses at all, even if the editors think the text is not original. Double brackets will be used.

I think Houghton might have finished his commentary before they made the UBS6 committee made that decision because his commentary makes it sound like verses are omitted. The entries omitting entire verses always say "omit verse" etc.

I would have expected Houghton to put the text in double brackets if double brackets were going to be used in the main text -- which is what Metzger did in his Textual Commentary. But the UBS6 introduction makes clear that double brackets will be used for passages like Luke 22:43-44 and 23:34.