On doing 'word counts' of biblical books

The mayhem behind brackets, Bible software, and the Byzantine and Western texts: can a method be found out of this madness?

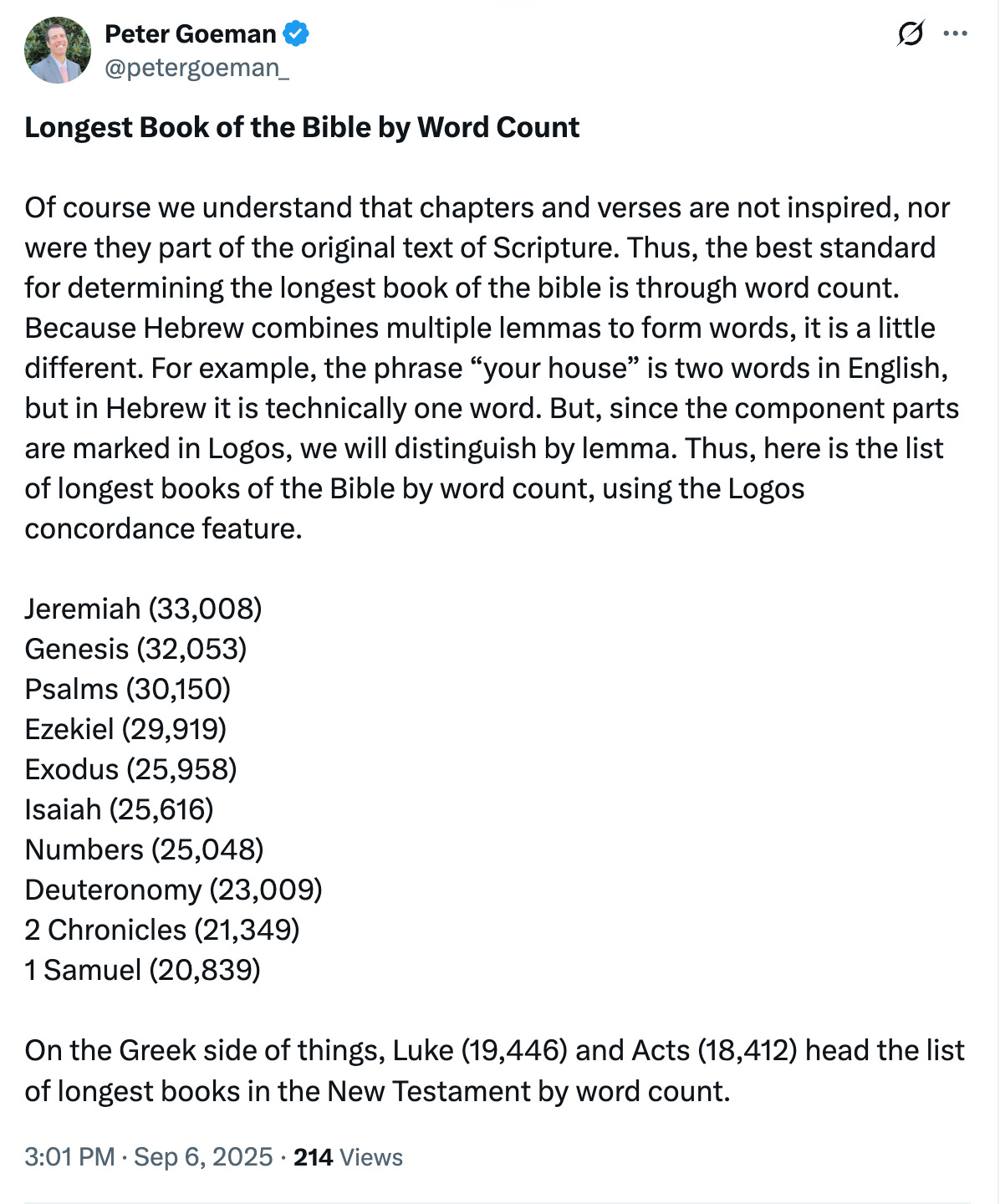

A recent Twitter/X post by Peter Goeman had my mind spinning once again over the issue of doing ‘word counts’ of biblical books:

This comes from a blog post on Goeman’s website, but was also part of a Twitter/X thread, entitled “What is the longest book of the Bible?”

Peter himself read through this post and said:

Peter and I have the same alma mater for our M.Div degrees, so this is not a major or fundamental disagreement. I like what he posts on Twitter/X and I’m sure he’s a great guy. This is just a humble attempt towards greater accuracy. I hope this can be an ‘iron sharpening iron’ (Prov 27:17) sort of exercise.

Is an exact word count of biblical books possible? No.

As a New Testament textual critic, I have to chime in with the caveat that producing word counts of biblical books is very difficult:

I would say it’s impossible to have an exact word count of biblical books since we only have manuscript copies (that disagree with one another) and modern editions based on those manuscripts. In other words, we don’t have the original autographs. Possessing the original autograph would be the only way to have an exact word count of a biblical book.

No one would dare say that we have the exact wording of the original Greek New Testament autographs in NA28 (or any other edition) — yet often we’ll see even scholars putting out exact word counts of the biblical books based on NA28 🤔

But … there is a careful and responsible way that we can approximate the word count of biblical books (just as we approximate the New Testament text through textual criticism).

Five issues to consider:

1. What edition/translation will you count from? And does your Bible software count non-biblical text?

Peter Goeman is probably using the Nestle-Aland 28 Greek New Testament for his word counts (but he doesn’t say). This is fine, but the edition used should be stated explicitly since there are other Greek texts available, such as the Tyndale House Greek New Testament, SBL Greek New Testament, Robinson & Pierpont’s Byzantine Textform, and the Textus Receptus.

These will all have different word counts than NA28.

And one issue of using Bible software to count words is that it’ll usually include the books titles as well (e.g. προς Ρωμαιους), so these need to be subtracted out to get a precise count for NA28. I use Accordance and it will count book titles when you use an asterisk (*) in a word search and limit the search to one biblical book. Another example of counting non-biblical content is the THGNT, which has a marginal note from minuscule 1 on the long ending of Mark, which needs to be subtracted out from a Bible software’s word count of Mark.

The same applies to the Hebrew Old Testament, but that’s not my speciality so I’ll focus on New Testament.

2. What will you do with the Byzantine text, Textus Receptus, and Western text?

Yes, you could say these are all wrong and just follow NA28, but these texts still exist nonetheless and you have to account for them.

2.1 Robinson & Pierpont’s Byzantine New Testament text is substantially longer than NA28’s text (the lower margin of Robinson & Pierpont’s edition list all textual differences from NA27, so you could have fun on your next vacation and count how much longer the Byzantine text is 😬).

And NA28 has not 100% shut the door on longer Byzantine readings. There are UBS5 {B} or {C} ratings with longer Byzantine readings, which means the editors were open to their inclusion. In other words, some longer Byzantine readings rejected in the main text by NA28/UBS5 could be the original text and would thus increase word count. (This is what the ECM does in a limited number of cases).

2.2 The Western text of Acts is about 8-10% longer than Westcott & Hort’s text of Acts, which is fairly close to NA28 (see Metzger’s Textual Commentary, p. 223). In the early 20th century, there were some who thought Western text of Acts was truer to the original (e.g. Albert Clark). But I don’t think anyone really thinks so anymore (if I’m wrong, please correct me).

In any attempt to provide word counts of biblical books, I think we should acknowledge the alternative texts and say explicitly if we are rejecting these alternative texts.

3. What will you do with the ECM and THGNT?

Both the new Editio Critica Major (ECM) and Tyndale House Greek New Testament make small moves towards longer Byzantine readings, and thus might have increased word counts compared to NA28.

The ECM text of Acts, Mark, and Revelation will be adopted in NA29, so the word count will change once again.

On the other hand, sometimes these two texts will be shorter than NA28 — but either way, these two editions should be accounted for.

4. A cross-comparison of editions is a decent starting place for producing a word count of a biblical book…

I prepared this for a paper presentation on Acts in 2024:

It’s a Google sheet than you can view: “Word count of Acts?” Everyone who views the spreadsheet has commenting privileges, to help fix mistakes or raise some other issue.

4.1 I added in the Latin Vulgate just for fun since our modern chapter system was created based on the Latin Bible, not the Greek Bible. Stephen Langton (who created the modern chapter divisions for Acts) wanted to create chapters of roughly equal length. The only way to test how well Langton did is to do a word count of the Latin Vulgate text of Acts (which won’t be Langton’s exact text, but it’s good enough as a start). But it is striking how the Latin Vulgate text of Acts is roughly 2,000 - 2,200 words shorter than the various Greek texts. This can’t be accounted for just by grammatical differences among the two languages. I need to look into this more by finding studies on the Latin text of Acts. But … Langton did not do a good job in making the chapters of Acts to be of roughly equal length 😩

4.2 Codex Bezae is a major representative of the Western text (yes, yes — this is disputed, but the basic point holds). Unfortunately, Bezae is not extant for all of Acts, so we can’t do an overall comparison. But you can compare specific chapters where Bezae is fully extant (* indicates the chapter in Bezae is fragmentary).

For example, Acts chapter 15 has 94 more words in Bezae than NA28. That’s substantial — although almost no modern text critic would favor the Western text of Acts.

I don’t include the ECM of Acts because there is no searchable version of ECM Acts.

5. But even my chart has problems — what about brackets in NA28 and {C}/{D} ratings in UBS5?

5.1 There’s hundreds of single bracketed readings [] in NA28, which indicate editorial uncertainty and which could have been omitted by the editors. In other words, the editors had a difficult time deciding between including or omitting the bracketed words.

If you omitted some or all of NA28’s bracketed words, there would be a substantial difference in word count.

5.2 NA28’s double brackets [[ ]] indicate passages that are clearly not original (according to the editors), but they chose to still include it in the main text (such as the long ending of Mark and Pericope of the Adulteress). Bible software will include these doubled bracketed texts in a word count, so these definitely should be subtracted out and will substantially change the word count of Mark and John.

5.3 There are {C} and {D} ratings in UBS5 which didn’t receive brackets. This is a major inconsistency that has been constantly pointed out in reviews going back to UBS1. Every {C} and {D} rating should theoretically receive brackets, but that’s not always the case in the UBS editions. These {C} and {D} ratings indicate high editorial uncertainty, so these are even more words that could be omitted and thus reduce word count in NA28 even further.

My chart of Acts above doesn’t take into account bracketed words and non-bracketed {C}/{D} ratings because it’s quite tedious work. But doing so would further improve my chart.

Does this all really matter??? 🧐

If we’re just interested in knowing the length of books, not really.

The fluctuation among editions will usually be a small amount. But Acts is a special case because the Textus Receptus and Western text are hundreds of words longer than NA28 (and the Byzantine text ends up adopting some of these Western readings while rejecting several Textus Receptus readings).

But I think this whole exercise shows two things: (1) When people give an exact word count with no alternative texts and no accounting for textual uncertainty, they are assuming NA28 to be the original text and are making no effort to untangle difficult textual issues. By ignoring other editions, they overlook variants that NA28 rejected yet some of those rejected readings (esp. those with {C} or {D} UBS ratings) could be the original text and affect interpretation.

(2) We get a sense of why there was so much backlash against Westcott & Hort and critical text advocates in the 19th century by those who favored the Textus Receptus. If Westcott & Hort (and by extension, NA28) were just omitting 10-15 words in a book, meh — who cares, it wouldn’t affect much. But the Byzantine text of Acts is ~220 words longer than NA28 and the Textus Receptus of Acts is ~360 words longer than NA28. That’s a substantial amount of additional content.

In other words, the difference isn’t just about adding some conjunctions and articles and prepositions. Interpretation and translation are affected.

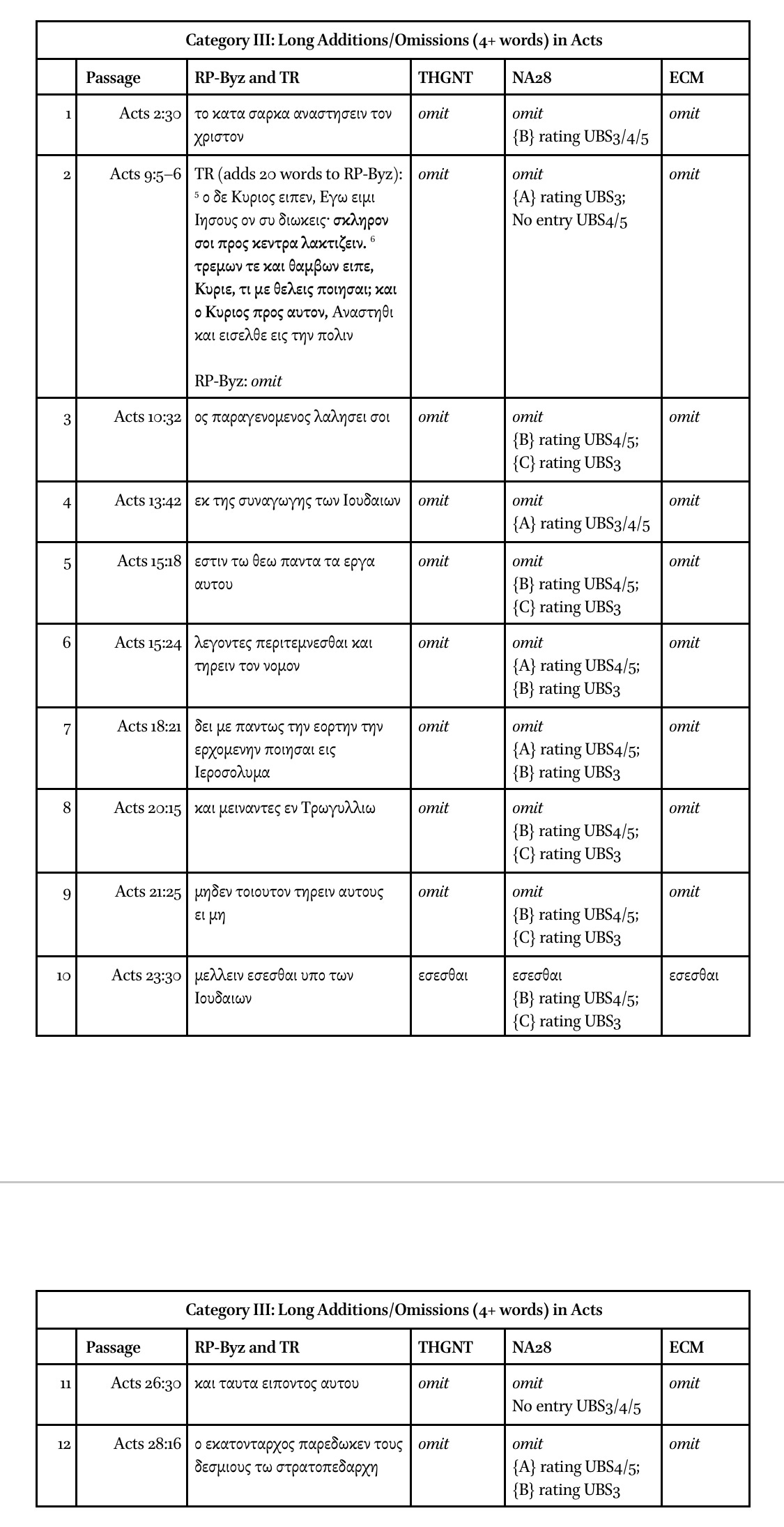

Here’s 12 passages in Acts where the Byzantine text and/or TR adds 4+ words and has a significant difference from NA28:

But even if we reject all the Byzantine longer readings in Acts (as both THGNT and NA28 do), we still recover reception history based on what scribes added and we learn how others read Scripture.

tl;dr — conclusion?

It’s really complicated to produce a word count of the biblical books because we don’t possess the original autographs.

What I would do is indicate which precise edition I am using and say something like “there are approximately 18,452 words in NA28’s edition of Acts, but this number could go down substantially if we took out bracketed text.”

I would also always include the Byzantine text as a comparison (which also has split Byzantine readings!) and say something like: “there are approximately 18,671 words in Robinson & Pierpont’s Byzantine text of Acts — roughly 219 more words than NA28. But this number could go down depending on how we handle split Byzantine readings.”

And usually the Textus Receptus and Byzantine text are pretty close in word count, but in the case of Acts, the Textus Receptus is roughly 140 words longer than the Byzantine text and 359 words longer than NA28.

So in the case of Acts, I would add something about the Textus Receptus: “there are approximately 18,811 words in the Textus Receptus — roughly 140 words longer than the Byzantine text or 359 words longer than NA28. This number could change depending how we handle minor variations among Textus Receptus editions.”

I know this isn’t as fun or as easy as giving an exact word count for all biblical books 😭 🥲

But my suggested method is closer to the truth and shows how important textual criticism is!!! 😬

p. s. — someone will probably object that Peter doesn’t say that he is giving an exact word count, which is true. But a sense of exactness is what comes across when where are no caveats, no language of approximation (e.g. “about/roughly/approximately 10,000 words”), no mention of other Greek editions.

p. p. s. — Back in April 2023, Patrick Schreiner did preliminary word counts for all the New Testament books; I had these same critiques of his initial version, so he revised it and produced a Word Count for New Testament Chapters (on Twitter/X). Patrick didn’t implement everything I suggest here, but he did take into account some of my points and offer more caveats.

p. p. p. s. — Our inability to give exact word counts should extend to Greek NT vocabulary lists. I’m maybe wrong, but the practice of giving exact word counts for NT Greek vocabulary seems to have coincided with the Nestle-Aland editions becoming a “new Textus Receptus” in the 1980s/1990s (e.g., many beginning grammars like Mounce; Wallace’s reader’s lexicon; Murray J. Harris on prepositions). Especially for words that occur very frequently (conjunctions and prepositions), it’s probably impossible to give a precise word count since even NA28/ECM/THGNT are so often uncertain about conjunctions and prepositions.

Also, thanks to Daniel Buck for pointing out an error (now corrected) on how much longer the Western text is.