Romans 5:1 in the Tyndale House GNT vs. Nestle-Aland 28

A revival of the subjunctive reading εχωμεν?

This is a revised excerpt from my dissertation’s discussion of Romans 5:1 (hopefully to be published with Brill):

Romans 5:1 is probably the most famous textual problem based on an ω–ο interchange that happens to be morphologically significant:

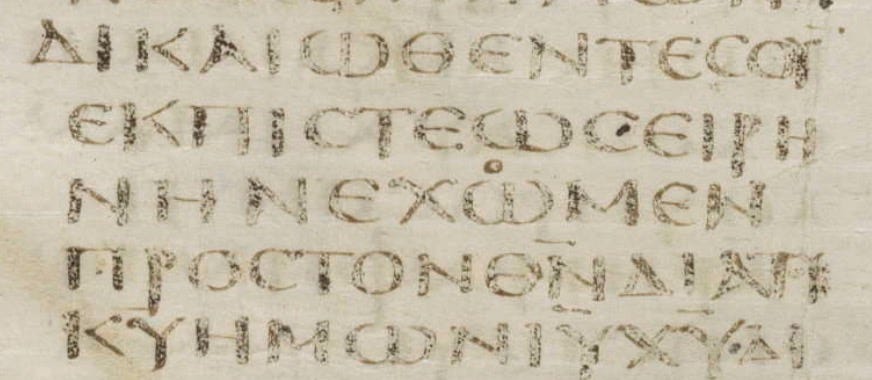

δικαιωθεντες … ειρηνην εχωμεν προς τον θεον THGNT; RP-Byzmg

“Having been justified … let us have peace with God”

δικαιωθεντες … ειρηνην εχομεν προς τον θεον NA28; RP-Byztxt; {A} rating UBS4/5; {C} rating UBS3

“Having been justified … we have peace with God”

The ω–ο interchange is a common type of textual variation that could have easily arisen due to the similar sound of omega and omicron during the Koine period. Based on papyri evidence, Chrys Caragounis concludes: “From the third century B.C. on, O and Ω interchange very frequently, which implies that if there had ever been any distinctions between them originally, these letters had now become equivalent.”[1]

Most often, the ω–ο interchange is not significant and can be categorized as an orthographic alternative or spelling “error.” However, the difference is significant in some cases where the omega creates the hortatory subjunctive and the omicron creates the indicative. This occurs in Rom 5:1; 14:19; 1 Cor 15:49; Gal 6:9; Heb 12:28.[2]

In Romans 5:1, the THGNT prints the subjunctive εχωμεν, while the NA28 prints the indicative εχομεν. The Byzantine text is divided. Peter Head (one of the THGNT editors) notes that the editions of Tischendorf, Westcott & Hort, von Soden, Vogels, Merk, and Bover all chose ἔχωμεν, and Head thinks that “[t]he manuscript evidence is firmly on the side of the subjunctive.”[3]

However, it is worth mentioning THGNT editor Peter Williams’s comment about the subjunctive reading: “And just how sure are we that εχωμεν is a subjunctive, rather than an indicative spelled with omega? . . . my vote would be for εχωμεν understood as an indicative. It seems to me to be the reading that best explains the other.”[4]

This caveat and nuance applies to all occurrences of the ω–ο interchange. We should not be quick to assume that the difference automatically leads to a subjunctive vs. an indicative since both readings would have been pronounced the same. And most people would have heard the New Testament orally, rather than have read the New Testament text and visually seen the ω–ο difference.

What is also interesting about Romans 5:1 is the change in certainty rating between UBS3 (published in 1975) and UBS4/5 (published in 1993 and 2014): UBS3 had a {C} rating, while UBS4/5 upgraded to an {A} rating, a two-step upgrade from being doubtful to being fully confident. The uncertainty from the 1970s faded away in the 1990s. Bruce Metzger’s Textual Commentary provides no explanation for the upgraded certainty.

The Editio Critica Maior (ECM) of the Pauline epistles is not yet available, but a comment from Georg Gäbel (research associate at the INTF) reveals that maybe the ECM of Romans will print a split guiding line between εχωμεν and εχομεν.

Gäbel’s review of the THGNT is semi-supportive of their decision, but criticizes the lack of patristic evidence:

In Röm 5,1 lesen wir den Konjunktiv ἔχωμεν (hier bedauert man das Fehlen patristischer Bezeugung, vgl. den Apparat des UBS Greek NT); diese Variationseinheit könnte angesichts der ebenfalls guten Bezeugung für den Indikativ und der Häufigkeit der ο/ω-Isochronie in den Mss. eine Kandidatin für den Verzicht auf eine Entscheidung zwischen gleichwertigen Möglichkeiten sein.[5]

English translation: “In Rom 5:1 we read the subjunctive ἔχωμεν (here one regrets the lack of patristic attestation, cf. the apparatus of the UBS Greek NT); this variation unit could be a candidate for abandoning a choice between equivalent possibilities, given the equally good attestation for the indicative and the frequency of the ο/ω-interchange in the Mss.”

Gäbel was one of the editors of the INTF’s Editio Critica Maior (ECM) of Acts and here he seems to be suggesting a split-line diamond reading, i.e., no guidance on the initial text. The uncertainty of UBS3 from the 1970s could return to the ECM of Romans (to be published early 2030s, probably).

[1] Chrys C. Caragounis, The Development of Greek and the New Testament: Morphology, Syntax, Phonology, and Textual Transmission, WUNT 167 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2004), 373.

[2] See the discussion of Rom 5:1; 14:19; and 1 Cor 15:49 in Caragounis, The Development of Greek and the New Testament, 541–45.

[3] Peter M. Head, “0220 at Romans 5.1,” Evangelical Textual Criticism (blog), February 21, 2006, http://evangelicaltextualcriticism.blogspot.com/2006/02/0220-at-romans-51.html.

[4] Williams says this in the comments section of Peter M. Head, “0220 at Romans 5.1,” Evangelical Textual Criticism (blog), February 21, 2006, http://evangelicaltextualcriticism.blogspot.com/2006/02/0220-at-romans-51.html.

John Wevers, who edited LXX Genesis in the Göttingen series, writes that “[t]he most common error is confusion of ο-ω. . . . At [Gen] 4:14, the coordinate future indicatives κρυβήσομαι καὶ ἒσομαι occur in the apodesis [sic] of a simple condition. The former is written with -ωμαι in 5 mss and the latter in 2 mss. These are, of course, not intended by the scribes as subjunctives but as indicatives.” John Wevers, “A Note on Scribal Error,” Canadian Journal of Linguistics 17, no. 2 (1972): 188–89.

[5] Georg Gäbel, review of The Greek New Testament, Produced at Tyndale House, Cambridge, ed. Dirk Jongkind, Theologische Literaturzeitung 144, no. 4 (2019): 331.