The ordering of the New Testament books?

Does order matter? And how else have the New Testament books been ordered?

In a recent podcast with Dirk Jongkind, we mention that the Tyndale House Greek New Testament has a different ordering of the New Testament books than most modern editions: the Catholic epistles come after Acts, instead of after the Pauline epistles.

This can be jarring since we are accustomed to finding Romans right after Acts 🧐

So why the did THGNT editors “mess up” the order of NT books?

The THGNT editors ordered the New Testament books based on manuscript evidence.

We don’t get a manuscript containing the entire New Testament until the fourth century with Codex Sinaiticus. Even after Sinaiticus, most manuscripts don’t contain the entire New Testament, but portions of it. According to Peter Gurry:

Only around sixty of our Greek manuscripts contain all twenty-seven books of the New Testament. Another 150 or so contain all but Revelation.

— Scribes & Scripture (Crossway, 2022), 86.

The most common grouping of writings into one codex were:

The four Gospels

Acts + the Catholic Epistles (Jas, 1-2 Pet, 1-3 John, Jude)

The 14 Pauline Epistles (Hebrews was considered Pauline according to the manuscript tradition)

Revelation

In other words, an entire “New Testament” would have been four separate volumes.

But keeping Acts together with the Catholic Epistles is well-attested, so the THGNT follows this custom.

The order of books in our earliest manuscripts containing the entire NT

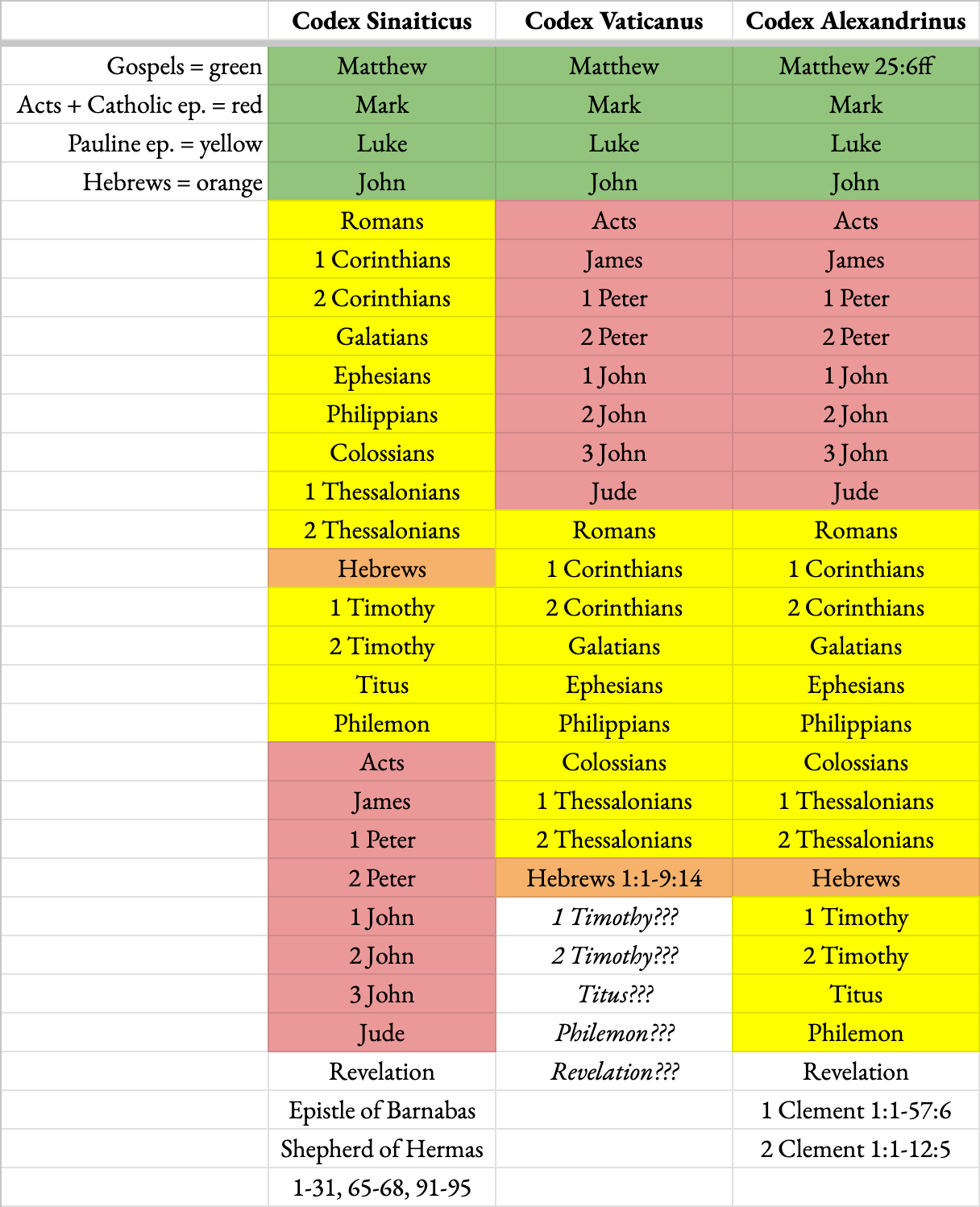

If we look at our earliest three manuscripts containing the entire (or almost the entire New Testament), we see the following ordering:

Notice how the THGNT is following the order found in Codex Vaticanus and Codex Alexandrinus.

And even though Codex Sinaiticus has the Catholic Epistles after Paul (like our modern Bibles and editions), it stills keeps Acts together with the Catholic Epistles because that was the custom among smaller groupings of the New Testament.

Does order matter?

What’s the effect of having the Catholic Epistles after Acts, instead of after Paul?

Well, this certainly follows the structure of Acts itself: Peter and James are major characters in the first twelve chapters of Acts. But from Acts 13 and onwards, Paul shifts to become the main character.

But I can also see how finishing Acts 28 with Paul preaching the gospel in prison flows nicely into reading the Pauline epistles.

I think we are often unaware of how the order in which we read the Bible matters. See the writings of Greg Goswell below for more reflection on this topic.

Other variations in ordering

Within these groupings, there are many other variations, but the following two variations are notable:

The so-called “Western” ordering of the Gospels has the sequence Matthew-John-Luke-Mark; this seems to give prominence to the two apostles and downgrades Mark to last 🥲

Within the Pauline epistles, Hebrews moves around quite considerably. Today, we have Hebrews at the end of the Pauline epistles after Philemon (although I guess you could also view its placement as the “beginning” of the General Epistles?). But as you see above in Codices Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus — Hebrews was placed after 2 Thessalonians and before 1 Timothy, in other words, it was placed between the epistles to churches and the epistles to individuals. But we have variations like Hebrews being placed between Romans and 1 Corinthians in P46. The THGNT editors thought about following the placement of Hebrews in Codices Sinaiticus and Alexandrinus, but decided they had already “messed up” the ordering enough and didn’t want to confuse users more.

I won’t offer all the evidence for these orderings here, but can point you to further resources on each of these topics…

RESOURCES FOR FURTHER STUDY:

Generally on the order of the NT books:

Bruce M. Metzger, “Appendix II: Variations in the Sequence of the Books of the New Testament,” in The Canon of the New Testament: Its Origin, Development, and Significance (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1987), 295-300.

Greg Goswell, “The Order of the Books of the New Testament,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 53.2 (2010): 225–41.

Gregory Goswell, Text and Paratext (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Academic, 2022), 54-75.

On the so-called “Western” ordering of the Gospels:

Matthew Crawford, “A New Witness to the ‘Western’ Ordering of the Gospels: GA 073 + 084,” JTS 69 (2018): 477–83.

Andrew J. Patton, “Greek Catenae and the ‘Western’ Order of the Gospels,” NovT 64 (2022): 115–29.

On the position of Hebrews among the Pauline epistles:

Charles P. Anderson, “The Epistle to the Hebrews and the Pauline Letter Collection,” Harvard Theological Review 59.4 (1966): 429–38.

William H. P. Hatch, “The Position of Hebrews in the Canon of the New Testament,” Harvard Theological Review 29.2 (1936): 133–51.

Robert W. Wall, “A Canonical Approach to the Paratext of Hebrews,” in Studies in Canonical Criticism: Reading the New Testament as Scripture (London: T&T Clark, 2020), 142-46.

P.S. Thanks to Jeff Cate for some helpful suggestions to improve the chart of Codices Sinaiticus, Alexandrinus, and Vaticanus.

Hey Nelson! Nice to find this article on substack :) I have been working on a PhD in a canonical approach under Dr. Ched Spellman. I recently posted this article on the Catholic Epistles, in case you are interested:

https://substack.com/home/post/p-185654072

It is my growing conviction that the DNA of the order you find in most of the codices (and also the canon lists!) originated with the Apostles themselves (at least to a degree). Works like Acts, Johannine Lit, and 2 Peter seem to "shape" the collections.

There's a lot to learn, but I was excited to find someone giving substack-attention to such things!